What appears to be an internal rift within the Department of City Planning could disrupt attempts to reform the city's parking policies for the Manhattan core, in the face of opposition from the powerful real estate industry.

Streetsblog reported yesterday that DCP is preparing significant revisions to parking policies in the Manhattan core. Limits on parking in Manhattan are a decades-old cornerstone of the city's traffic management policies, but developers know how to game the rules and take advantage of loopholes, leading to the construction of large new garages in some of the most walkable neighborhoods in the country. Parking experts praised DCP's reform package for tightening the rules and laying out an updated approach to parking policy appropriate for a dense urban setting.

Those plans are still just a draft, however, and DCP's final proposal could look much different. The powerful real estate industry is mobilizing against not only the proposed reforms, but existing parking limits as well. Meanwhile, factions within DCP seem intent on undermining the draft parking reforms, while the top of the department appears rudderless on the issue. Lately the City Planning Commission has issued a handful of pronouncements about the relevance of parking policy to a good pedestrian environment, but Planning Chair Amanda Burden has yet to make a sustained public stand on matters of off-street parking.

Any adjustment to the city's parking rules must go through the City Council, where the influence of the real estate industry will be felt. And the industry's lobbying arm, the Real Estate Board of New York, wants to undo parking limits already in effect in Manhattan.

Currently, developers of new housing can't attach parking to more than 20 percent of residences below 60th Street or 35 percent of residences below West 110th and East 96th Streets. "We would like to see those maximums raised to accommodate the auto ownership in those neighborhoods," said Mike Slattery, senior vice president for REBNY. A more detailed set of real estate industry recommendations drafted by the law firm Kramer Levin [PDF] opposes most, but not all, of the draft parking reforms currently circulating inside DCP.

Interestingly, REBNY's rationale for opposing parking maximums echoes DCP's own studies. Borrowing a line from DCP's 2009 residential parking study, Slattery argued that car ownership is independent of parking supply and instead determined mainly by household income. The implication is that parking maximums only lead to parking shortages, not to reduced car ownership and driving.

The argument is faulty (more on that below), yet DCP itself continues to perpetuate it. Despite the department's forward-thinking draft proposal to reform parking policies in the Manhattan core, not everyone seems to be on board. The department's transportation division houses a faction determined to provide the city with a steady supply of new parking spaces, even in the heart of Manhattan. The division is at work on a new study of public parking in the Manhattan core, and a draft recently obtained by Streetsblog [PDF] mainly serves to justify the need for more parking.

The presentation on the parking study [PDF] states: "Vehicle registrations in all of Manhattan increased 39 percent between 1982 and 2009, despite the 1982 policy to reduce parking." Like Slattery, DCP's transportation division is arguing that parking maximums do not, in fact, reduce car ownership. It's the mirror image of previous claims from DCP that parking minimums do not induce car ownership. The argument is also riddled with flaws.

Parking construction is mandated uptown, so it's completely improper for DCP to lump vehicle registrations inside the Manhattan core together with registrations outside the core. "This is, near as I can tell, an example of the sloppy nature of these studies. They're fast and loose with their definitions to support the points they want to get to," said Dave King, a planning professor at Columbia University. "There's still hundreds of thousands of people north of Central Park who are all subject to parking minimums."

Rachel Weinberger, a University of Pennsylvania planning professor, noted that the actual change in car ownership in the Manhattan core is consistent with the assertion that the parking maximums have worked.

Similar errors abound in DCP's study, and all point in the same direction. Finding that car ownership in Manhattan is linked to income and parenthood, DCP concluded that "demographic changes among Manhattan residents have led to an increase in the number of private vehicles in the Core." Again, the intent is apparently to dispel the idea that parking regulations affect car ownership rates. But correlation is not causation. It could be that the creation of more parking caused more high-income families to move to Manhattan.

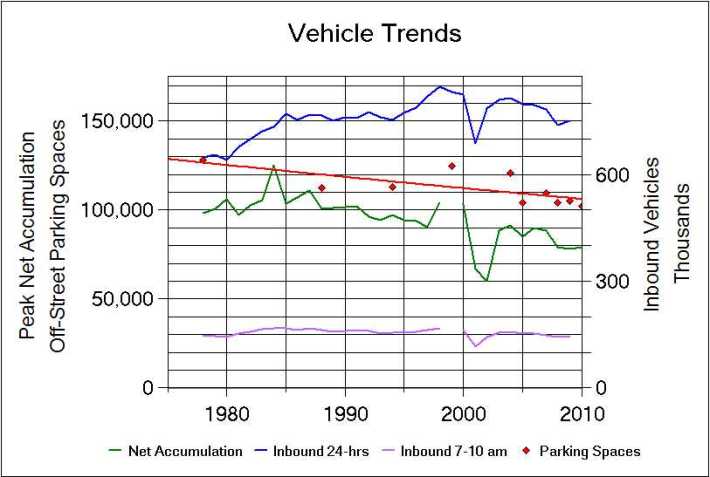

It could also be a coincidence, as when DCP found a strong correlation between finance-sector employment and the number of vehicles entering the Manhattan core. The department interpreted that to mean that structural economic shifts rather than parking policy affect travel behavior. However, environmental planner Dan Gutman crunched the numbers himself and found that interpretation wanting. Even though finance employment has risen, he said, "hub-bound morning peak (7-10 am) volumes have remained essentially flat since 1978." Since most high-paying finance jobs have daytime hours, it doesn't appear to be the case that new financiers are crowding the streets.

Instead, Gutman found that total vehicle accumulation in the central business district, the sum of all cars parked and driving in the area, declined in line with decreases in the parking supply. "This seems to imply that the increase in 24-hour hub-bound entries was largely related to through traffic or possibly other traffic during evening hours, and that reduced parking may have had the intended effect of reducing vehicle accumulation," said Gutman. "Thus the 1982 parking policy may have been a striking success rather than a failure."

Perhaps the most fundamental problem with DCP's study is that it tallies up the benefits of parking without accounting for its costs. The authors are sure to note that "there will always be a need for people with medical conditions to drive." Drivers entering Manhattan for entertainment or shopping trips, the report states, "should not be discouraged from parking in the Manhattan Core. They are a user group which generates revenue for the city and since they are likely to travel during off-peak hours and carpool, they do not create additional peak-period traffic congestion."

No doubt shoppers bring revenue to the city, but so would the additional retail space that could be built in place of a parking garage. DCP's report neglects to mention that. Likewise building more housing instead of parking would reduce rents for everyone. DCP officials, from director Amanda Burden to sustainability director Howard Slatkin, have publicly articulated some of the costs of parking in the past, but none of those costs were tallied in this study.

The pro-parking tenor of DCP's Manhattan core study is difficult to square with the draft parking reforms proposed by the department. Inside DCP, it seems, support for more progressive parking policies does not run deep.

Any parking reforms will have a difficult path forward, given the internal divisions at DCP, the opposition from the real estate industry, and the political difficulty of moving progressive parking policies through the City Council. Unless Amanda Burden shows leadership on the issue, a promising initiative to plan for a more sustainable city might not have much of a future.