The crucial urban issue of our time is the collapse of the region’s transit lifelines, not a distant superhighway to serve 30,000 affluent, largely white, male suburban motorists.

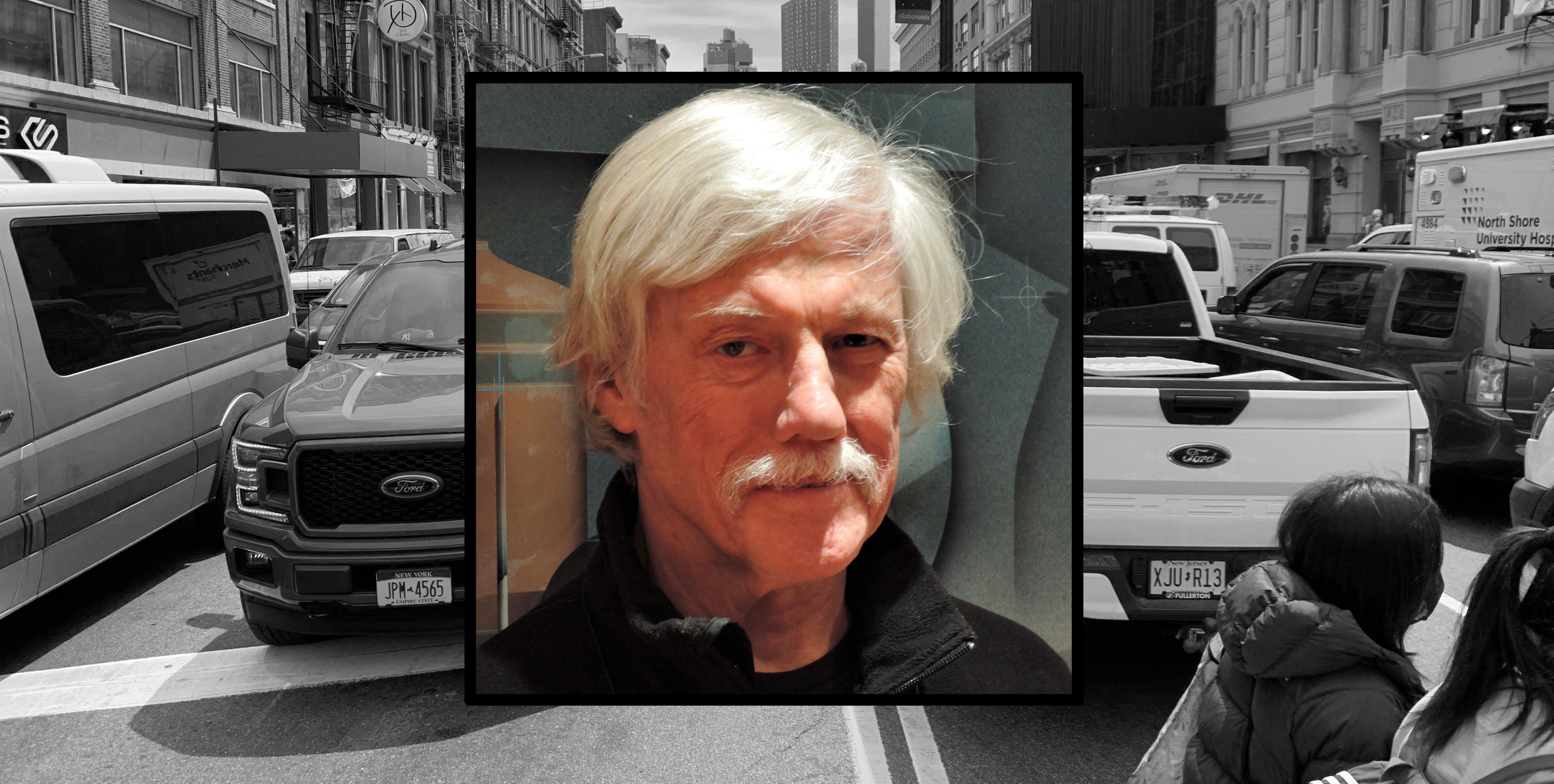

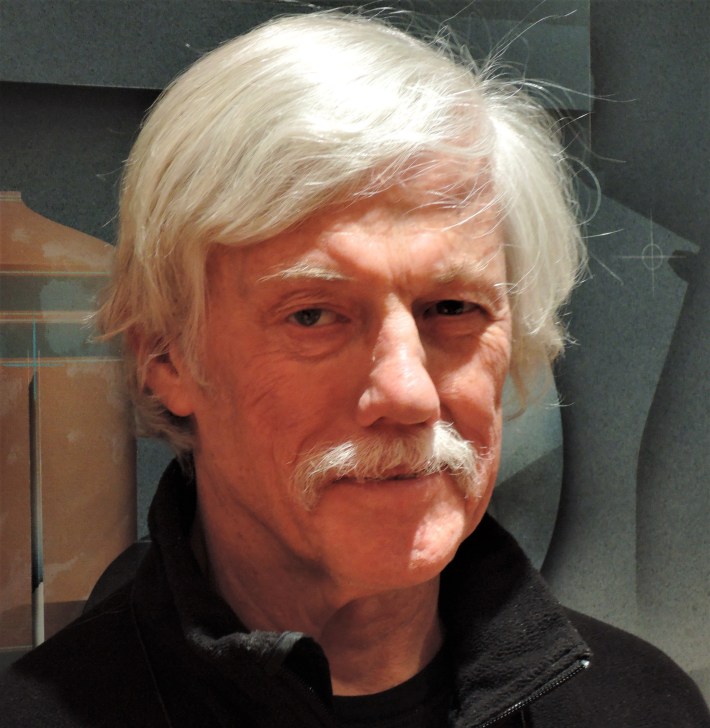

That sentiment, seemingly ripped from today’s headlines, appeared 44 years ago in the Daily News. Its author, renegade engineer, clean air pioneer and mass transit champion Brian Ketcham, died yesterday in New York City.

Ketcham's death resulted from injuries suffered in a recent fall, according to his son, the writer and journalist Christopher Ketcham. He was 85.

The object of Ketcham’s 1980 epigram, one of innumerable broadsides from his swashbuckling career, was Westway, the Manhattan highway boondoggle he helped vanquish. Brian also helped propagate two crucial if still not fully mainstreamed transportation paradigms ― induced traffic and congestion pricing. He was also a founding father of the urban bicycling-advocacy organization Transportation Alternatives and a force in establishing the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, in 1973 and 1993, respectively.

Brian Ketcham entered the world on May 19, Malcolm X’s birthday, in 1939, in Tacoma, Wash. and spent his boyhood in California’s Central Valley. If he didn’t have Detroit Red’s DNA, he had some of his intensity. Brian was passionate and driven. He didn’t suffer fools. He was outspoken and impulsive.

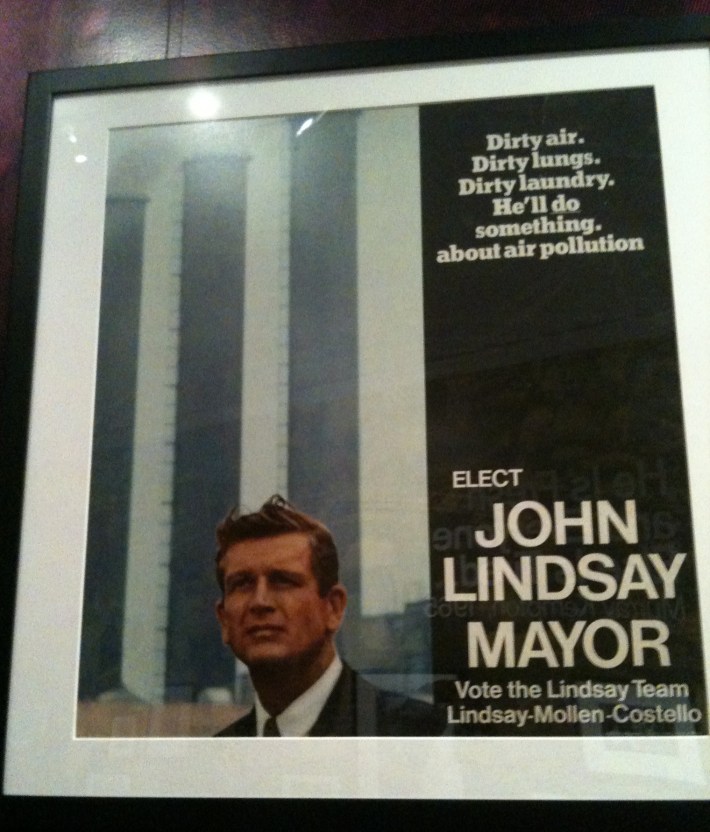

I don’t know much about Brian’s boyhood. Like other Californians at mid-century, he was enthralled with cars, especially their aerodynamism, which led him to engineering programs at Case Western Reserve in Cleveland and M.I.T. and a stint with Curtiss Wright Corp. in New Jersey. Stirred by New York City’s charismatic new mayor John Lindsay and intent on putting his combustion know-how to good use, Brian made his way to Manhattan in the late 1960s.

Lindsay’s insurgent 1965 mayoral campaign had targeted air pollution. Car and truck engines along with Con Edison power plants burning sulfurous oil were said to be dumping two cigarette packs’ worth of noxious smoke and gases a day into New Yorkers’ lungs. Once in office, Lindsay cleared the deadwood from the city’s Bureau of Air Resources and stocked it with young Turks. Ketcham signed on and soon secured federal funds to establish a Motor Pollution Control group within the bureau.

Under two hoods ... engine testing in industrial Brooklyn

Uncontrolled tailpipe exhaust is a witch’s brew of a dozen or more gases and particles. In the 1960s, no one knew precisely how much of each, or how emissions varied with driving circumstances ... or how far emerging emission-control tech could drive down emissions. In less than a year, Brian’s team built an automotive-emissions testing station in an abandoned storefront on Frost Street in Williamsburg, hard by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Its crown jewel was a contraption that simulated urban driving cycles and measured their emissions — the nation’s first “dynamometer.” In 1970 Ketcham and Frost Street had more catalyst-equipped cars and trucks under test than the entire worldwide auto industry.

The findings from Frost Street were a mixed bag for clean air hopes. New tailpipe catalytic converters could indeed cut carbon monoxide and volatile organics from car exhaust — evidence that helped pro-air quality forces in Congress beat back auto industry efforts to water down Clean Air Act standards.

But banning leaded gasoline that befouled the catalyst would take half-a-decade or more. New York City air would remain toxic, especially at ground-level.

The NYC Transportation Control Plan

Brian had an epiphany: What was strangling New York was bigger than car exhaust, it was cars themselves ― their insatiable bulk that swallowed road space and rendered city streets human sacrifice zones. Urban driving, he deduced, was underpriced (ditto on-street parking), and underfunded transit alternatives couldn’t compete. Not just meeting air standards but maintaining urban viability required a multi-pronged plan to reduce driving, beginning in Manhattan’s Central Business District: cab stands, bans on taxi cruising, exclusive bus lanes, parking shrinkages, plus fines and tolls for bringing subways and buses into states of good repair.

Thus was born, in 1973, the Lindsay mayoralty’s eighth and valedictory year, Ketcham’s kaleidoscopic Transportation Control Plan. Implementing any one element was a tall order, but the undisputed Mt. Everest was to toll the city-owned East River and Harlem River bridges ― an essential strategy to dissuade some motorists from entering Manhattan while raising money for transit from the rest.

Congestion pricing, in other words, if only between Long Island and Manhattan and the Bronx and Manhattan. Alas, seamless electronic tolling was then just a gleam in Columbia University economist (and pricing theorist) Bill Vickrey’s eye. The notion of cutting pollution while balky toll booths backed bridge traffic deep into downtown Brooklyn and Long Island City was fatally oxymoronic. Lindsay’s successor as mayor, Brooklyn clubhouse pol Abe Beame, approved the plan to avert the loss of $2 billion in federal aid tied to clean-air progress, and then tossed the tolls into the trash along with almost all of Brian’s allied measures.

Nevertheless, congestion pricing entered public discourse. Half-a-century later, Kathy Hochul’s loss of nerve stole Brian’s victory lap. Ironically, by helping usher in cleaner tailpipes, he and his Frost Street lab neutered a killer argument against urban car use that even Hochul might not have countermanded.

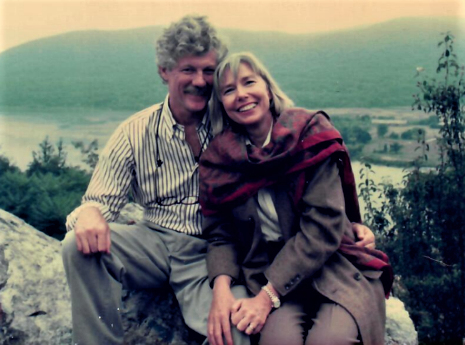

Carolyn and Westway

Enter Westway, the superhighway-cum-real-estate-megaproject beloved by New York’s coterie of financiers, fixers, unions, NY Times editorial writers, and successive mayors and governors. The only objectors were ragtag West Village dwellers and other Jane Jacobs acolytes who, with Lindsay’s tacit support, had slain Robert Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway in the 1960s.

Also enter, into Brian’s life, fellow Lindsay alum Carolyn Konheim, co-founder of the grassroots urban ecology think-tank Citizens for Clean Air. Effervescent Carolyn, a born people-person, was yin to Brian’s nose-to-the-grindstone yang: a communicator, a coalition-builder, a synthesist. Their attraction was immediate and mutual. In the mid-1970s, they left their respective marriages and began to conjoin their lives and careers.

Both had also left their city jobs, pushed out by the revanchist Beame crowd. Westway was the leviathan they could not let pass. Where its promoters promised unjammed traffic, riverside parkland and a reinvigorated economy, Westway antagonists saw fat-cat bonanzas, “induced” traffic lured by the adrenaline rush of initially faster commutes, and emissions overspreading the city.

Westway would bend both Brian’s career arc and personal life. Teaming with Carolyn under the Citizens for Clean Air banner, he began to grasp “public participation” as a counterweight to the new post-Moses power brokers. Induced traffic was no longer an intriguing sidelight but a worm at the heart of road-building, not just in dense Manhattan but everywhere. Brian would wield induced traffic as kryptonite against the road lobby. But calling out Westway’s true colors would make him a pariah.

So committed to Westway was New York’s permanent government, and so damaging were Brian’s expertise and imprimatur, that his unbridled opposition led to his getting blackballed from consulting assignments that would have been his bread and butter. Westway would fall ― as Nicole Gelinas’s forthcoming book Movement will recount ― but the remainder of his career would be spent largely in professional limbo.

Many other players did in Westway, among them crusading journalists Sidney Schanberg and David Gurin, organizer and roadbuilder nemesis Marcy Benstock, litigators Al Butzel and Mitch Bernard, Hudson River-defending Natural Resources Defense Council attorneys Ross Sandler and David Schoenbrod, transit “trade-in” champions Gene Russianoff and Dick Ravitch. To this impressive cast, Brian lent highway-engineer gravitas. His warnings that a west side mega-highway would compound, not alleviate, Manhattan traffic and congestion didn’t just subvert the steamroller, they gave outgunned opponents courage to fight on.

Tallying Vehicular Harms

I came into Brian’s life, and vice-versa, around 1990. We had crossed paths any number of times, beginning in 1971 when auto enthusiast and itinerant journalist Sam Julty interviewed Brian on WBAI, and my reward for phoning in was an invite to meet up at Julty’s Flower District loft. Apart from the hypermasculine vibe ― Julty and Ketcham both presented as “man’s men” ― what stunned me that day was Brian’s revelation that the chemical compounds in car and truck tailpipe spew could be named and measured. A new world of quantitative analysis opened before me.

By 1972, with a groundbreaking study of electric power plant pollution to my name, I was toiling at the same municipal superagency as Brian, the NYC Environmental Protection Administration, which had absorbed the Bureau of Air Resources. Except Brian was king of Frost Street in Brooklyn, and I was a junior policy analyst in Manhattan, my portfolio limited to power plants and energy efficiency. I thought daily about car exhaust and traffic, especially as a fledgling bike commuter. But Ketcham’s kingdom might have been Outer Mongolia, it was that distant from mine.

Even in the mid-1980s, when I took the reins at Transportation Alternatives, the scrappy car-fighting outfit Brian had co-founded in 1973 (with Gurin, Fred Kent, Barry Benepe and Roger Herz), Brian and Carolyn remained mythic figures toiling at urban planning, whatever that was. What finally linked our orbits was a talk Brian gave at TA’s 1991 Auto-Free Cities conference, enumerating the circles of personal and social harm caused by driving ― from tailpipe exhaust, noise, gridlock, and blunt force trauma ― calculated for Manhattan, New York City, and the entire United States. Brian’s methodology was a bit on the broad-brush side, but his cataloguing of car and truck “externalities” inspired and guided a new generation of advocates throughout the U.S. taking up analytic arms against automobile dependence.

Family

Around 2000, Carolyn’s health began to falter. Though her resolve to fix New York City and heal the world never weakened, her gait and speech went off-kilter. Parkinson’s Disease. It progressed, as it does, and Carolyn deteriorated. What didn’t waver was Brian’s devotion. For most of the aughts and all of the teens, he and his daughter Eve tended to her around the clock. She died in 2019.

Brian Ketcham is survived by his daughter Eve, son Christopher, and granddaughters Léa and Josie. Christopher and I have been close friends since the late 1990s, collaborating on stories for the Intercept and the Carbon Tax Center. He carries his father’s fierceness into his journalism, as I endeavor to carry Brian’s work forward into policy and practice.

Author’s note: The epigram heading this post isn’t online. It's in Nicole Gelinas's forthcoming book and comes from the Aug. 28, 1980 Daily News story, “EPA Putting New Curve in Westway.” The many loving comments appended to my obit for Carolyn were lost during a recent Streetsblog digital makeover.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated all the bridges comprising Ketcham's 1973 Transportation Control Plan. Thanks to "Gridlock" Sam Schwartz for flagging that.