In 2011, the City Council passed a law requiring the Department of Transportation to bring new bike-lane proposals to local community boards — a process that can solicit valuable community input, but too often delays or derails the very projects it is designed to facilitate.

The good news, however, is that there may finally be the political appetite for improving such consultations. Council Member and incoming Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso has proposed a bill to repeal the 2011 law and to replace it with a more streamlined, efficient approach.

Community boards will still have a role, but Reynoso’s more fast-paced timetable for community comments and recommendations will ensure that, by giving community boards a deadline, they cannot simply endlessly delay or even run out the clock on proposals.

The next City Council should take up the Reynoso bill and then-Mayor Adams should sign it. But they should not stop there. Here are three more ideas for making Gotham the world’s biking capital:

- The mayor and the Council must give the DOT a mandate to build the infrastructure our city needs. Council members should give the DOT the political cover to make needed safety improvements. The DOT can still consider practical issues, flaws, and opportunities identified by the community, but should move expeditiously to implement the best possible plan — rather than no plan at all. We need an ambitious process to match the historic demand for bike infrastructure, bus lanes, open streets, slow streets, and more.

- We must broaden our narrow conception of who the “community” is. Too often, the community is defined as those who have the time or ability to attend a community board meeting. This excludes our neighbors who are working at night; those who don’t have Wi-Fi access to log on to a Zoom meeting; those who deliver our meals using the very bike lanes that community boards decry. Parochial definitions of “community” will inevitably result in parochial decisions.

- The city should provide data on how many car owners sit on community boards. Board applications should ask applicants if they own a car or ride a bike, and elected officials should encourage non-car owners to join these boards. Community boards are often not representative of their communities. Nearly six in 10 New Yorkers don’t own a car, and only 22 percent of Manhattan households own a car, yet many boards have more car owners than not. Our community boards must be more socio-economically and racially diverse and should include more renters, too. Progress in this area will fall to our borough presidents.

New York City is in the midst of a bike boom. From 2008 to 2018, daily cycling grew by 116 percent. The pandemic dramatically accelerated New Yorkers’ embrace of cycling as an alternative way of getting around the city: Citi Bike demand more than doubled and shops across the city ran out of bikes to sell. Cities around the world are responding by building hundreds of miles of new bike lanes and, crucially, expanding bike parking. Mayors such as Paris’s Anne Hidalgo acted swiftly, recognizing the opportunity to combat climate change with carbon-free transportation that actually speeds up traffic and reduces congestion.

Yet, the city’s bike lanes are constantly obstructed: Garbage, snow, illegally parked cars, delivery trucks, and more make these lanes dangerous and impassable, while the city prioritizes the more than 75 percent of street space dedicated to cars. New Yorkers deserve a plan for clearing these blockages, but we also deserve a vision for navigating a political obstacle: community boards.

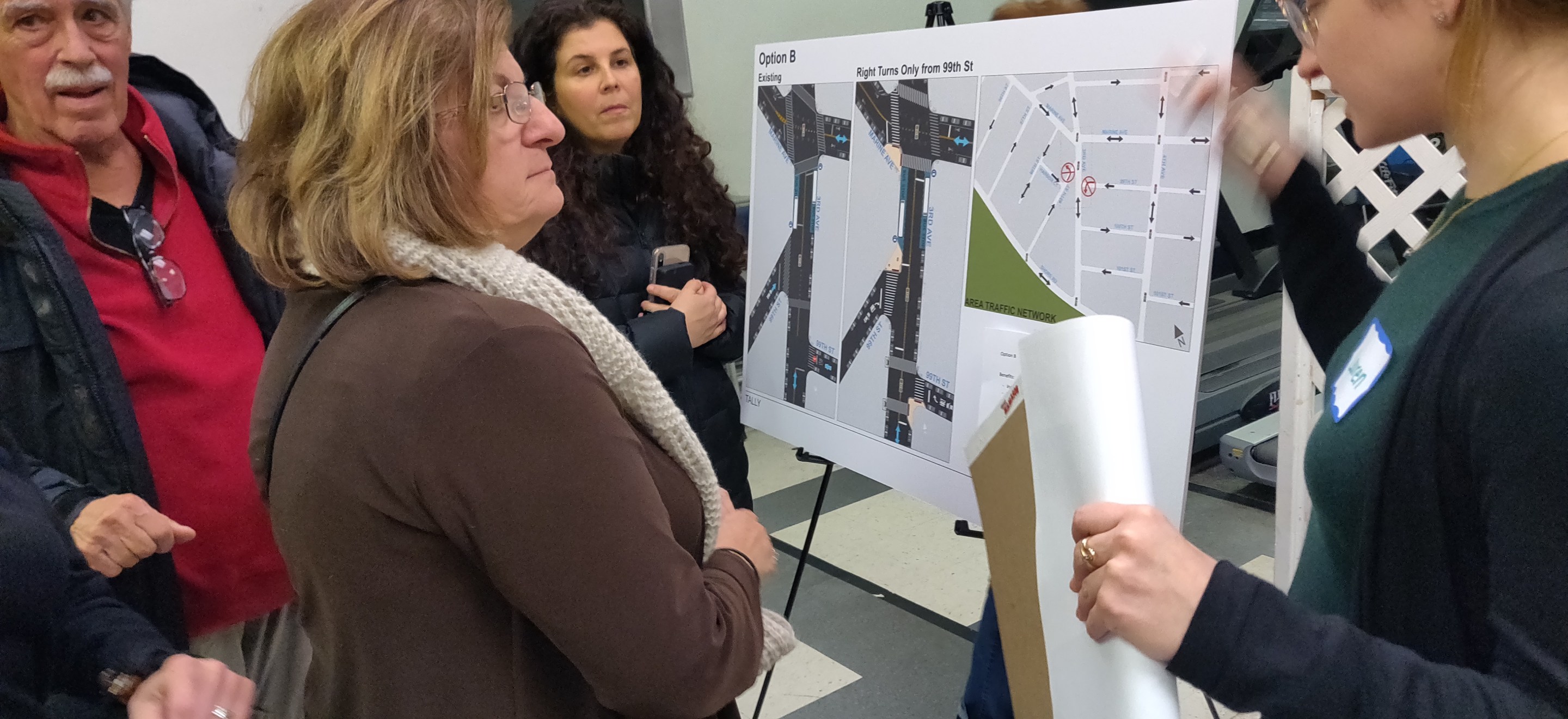

My community board, on the Upper East Side, asked the DOT in 2015 to propose crosstown bike routes. More than five years later, it took three meetings and nine hours until we finally voted to support making permanent two crosstown bike lanes on East 61st and East 62nd streets.

I’m often proud of the work we do, but such drawn-out processes and delays are unacceptable. DOT's overly deferential attitude toward community boards means that too many important safety improvements are being slowed or stopped. Two years ago, the DOT caved on its proposal for crosstown bike lanes in the East 80s, leaving cyclists like myself to navigate car traffic to get to and from Central Park. In 2011, the DOT abandoned on-street bike lanes in Bay Ridge, creating an eight-year delay. In Sunnyside, where a delivery cyclist was killed in 2017, it took more than a year for the DOT to announce the installation of protected bike lanes over the local community board’s opposition.

The bureaucratic delays go beyond bike lanes. Community boards can undermine accessibility improvements – such as new subway elevators and sidewalk redesigns, open streets, and other plans – that make our streets safer for all. Whether the DOT allows community boards to veto street design has profound consequences for safety, mobility, and our environment. Lives are at stake: Last year, 27 cyclists were killed, including 35-year old Sarah Pitts. As her brother put it, “There’s a clear mismatch between the importance cycling has taken on, and the city’s ability to make sure people protecting themselves from COVID are also protected while biking.”

In 2021, voters elected a wave of new leaders with bold plans for safe, complete, and accessible streets. Let’s make sure those plans become reality, and that we remove the obstructions in our path — both the physical and political.

Billy Freeland (@BillyFreelandNY) is an attorney, member of Community Board 8, and former candidate for City Council in District 5, which includes the Upper East Side, Roosevelt Island, El Barrio, and Midtown East. The views here are his own.