Street vendors have emerged as an issue in the mayoral campaign, after this week Andrew Yang made — and walked back — comments calling for more enforcement, and Scott Stringer went after him tooth and nail.

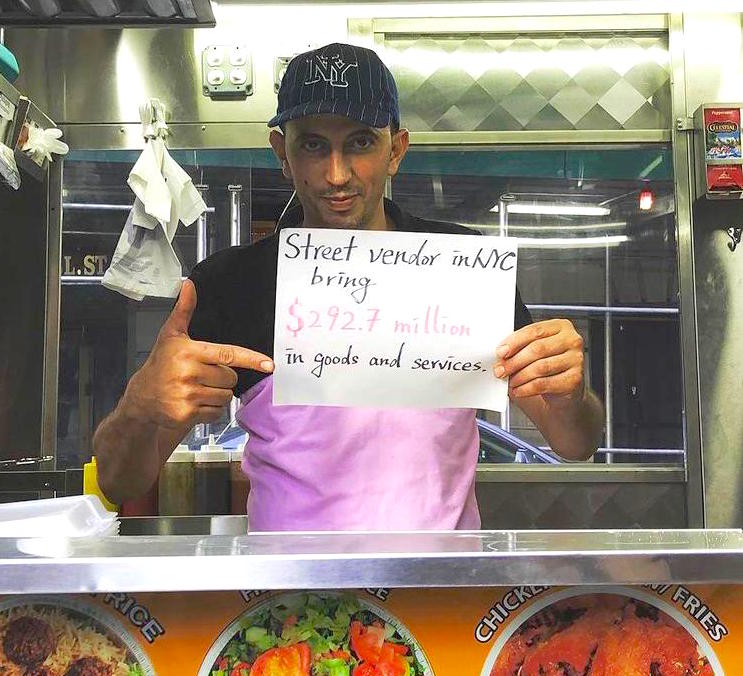

There are as many as 20,000 street vendors in NYC — and they are all part of the fabric of our city.

— Scott Stringer (@scottmstringer) April 12, 2021

This is a community that had to fight to survive during the pandemic, and were excluded from COVID-19 relief, because of leaders who failed to see them and their contributions. pic.twitter.com/VdxE7HDwvs

The back-and-forth between candidates misses the point, however: Calls for more enforcement against street vendors are nothing new and illustrate the historical and unfair imbalance between vendors and other small businesses. What vendors need from the next mayor are policies that encourage entrepreneurship and reduce barriers to viability. Like these:

Preserve and expand permits

In January, the City Council passed Intro 1116, which will raise the number of mobile food-vending permits, which have been capped since 1983. The lack of permits, and ensuing high demand, created an underground market in which permits command up to 100 times their price. Intro 1116 authorizes 400 new permits yearly for 10 years, beginning in July 2022.

Many vendors won’t feel the effects of the reform for years, if ever, however. The new permits will go first to those on the city’s waiting list (which was closed in 2007), as well as those who have been vending for the past five years. This is an admirable way to prioritize those vendors who have been working under an unjust system, but the best solution simply would be to lift the cap. The State Senate is debating a bill that would do just that.

The measure is not as radical as some might think. California, for example, enacted the Safe Sidewalk Vending Act in 2018, prohibiting localities from capping the number of street vendors. We don’t limit the number of restaurants or hardware stores. Given the many vendor siting restrictions that ensure pedestrian safety, why should the city limit the number of vending businesses?

Intro 1116 provides some relief for food vendors, but a cap of 853 — in place since 1979 — remains on the number of non-food vendor licenses. The next mayor, tasked with ensuring the city’s economic recovery, could create thousands of jobs by supporting more such licenses.

Adding more sidewalk businesses need not be hard or controversial. In the teeth of the COVID-19 pandemic last year, the city quickly issued more than 10,000 outdoor-dining permits, enabling restaurants to use the sidewalks and streets. Outdoor setups for retail stores soon followed. This movement reminds us that an activity is only “unlicensed” until a license is available. Policies and rules can change, especially during an emergency. Laudably, we reimagined our public space in a bid to provide a lifeline to restaurants and stores. Our next mayor should be thinking of the original sidewalk businesses — street vendors.

Expand vending locations

It is not easy to operate any small business in the city, but vendors have it especially tough. Even if they obtain a license and permit and find an unrestricted street and legal sidewalk spot, vendors must deal with the ever-changing sidewalk conditions and attempts to displace them. Vendors need to be part of the discussion when there are changes to the public space that they depend on for their livelihood. Private entities, such as business-improvement districts and real-estate owners, sometimes don’t view vendors as compatible with their vision of the public space, so they will place planters in known vending locations or enlarge sidewalk tree pits so as not to leave enough space for vending carts.

Such actions highlight the double standard that exists between vendors and these more powerful interests. When real-estate owners try to evict vendors unlawfully, vendors have little recourse. The city is quick to act, however, when complaints arise about vendors.

More benignly intended, but still severe, displacements can occur when the city installs sidewalk fixtures such as Citi Bike docking stations, way-finding signs, and bicycle racks. Vendors do not oppose these important parts of NYC’s transportation network, but before the city installs any street or sidewalk fixture, it should perform a good-faith “survey” to see if any vendors would be affected, which shouldn’t hinder city planning and would ensure vendors’ often-vulnerable locations. The city also should have a zero-tolerance policy for private actions that displace vendors.

Finally, the next mayor should support a wholesale review of the “restricted street” lists for vendors, which bar food and general vendors from various locations on different days at different times. The lists date from a now-defunct Street Vendor Review Panel, a Giuliani-era body that had no street-vendor representatives. During its tenure, the panel closed 130 blocks to vendors and opened not a single one. Vending spots need to be preserved and more “restricted” blocks opened.

Ensure access to assistance

The pandemic exacerbated many longstanding inequalities in our society — as was made clear when, initially, much government assistance designed for small businesses actually went to larger businesses. Many vendors couldn’t obtain any government assistance because of their immigration status or the informal nature of their businesses. For example, many vendors have cash-based businesses and can’t easily generate the documentation necessary for qualifying for loans and other assistance. Language and technological barriers also prevent many vendors from benefiting from government programs.

The Kafkaesque system that has existed for too long in New York City entrenches the vulnerability of vendors and makes it difficult for them to navigate the processes in place for small-business assistance. For example, requirements for current licenses complicate applications for many food vendors who do not have their own permit (or any permit) because of the longtime, unfair cap; others have expired licenses which they cannot renew because of tickets received. Applications for assistance should be flexible and accept documentation such as sales- or income-tax returns, NYS Sales Tax IDs (which many vendors possess), and even expired licenses. Vendors need easy access to grants and loans based on documentation requirements they can fulfill.

Our next mayor should listen to vendors about what they need to play their part in the city’s recovery and ensure that all small businesses receive the support they need to thrive.

The Street Vendor Project (@vendorpower), a membership-based organization that is part of the Urban Justice Center, works to defend the rights and improve the working conditions of the 20,000 people who sell food and merchandise on city streets.