The next chapter of the Department of Transportation’s long-awaited rebuild of Atlantic Avenue — one of the city’s deadliest corridors — won’t likely start until 2021, according to Council Member Rafael Espinal, Jr., whose district includes the project’s Brooklyn end.

The late anticipated start of the construction undoubtedly will disappoint those who have clamored for changes on the unsafe street. Speeding drivers on Atlantic constantly endanger both pedestrians and cyclists, with 20 killed and more than 1,100 injured since 2012 along the entire 10 miles from New York Harbor to Jamaica, according to data compiled by CrashMapper. In all, there have been 19,589 crashes — roughly seven per day.

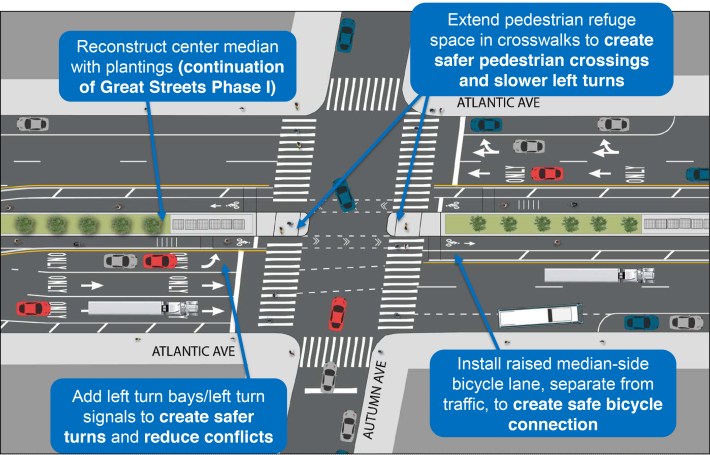

When complete, the mile portion of Atlantic Avenue between the notorious Logan Street in East New York and Rockaway Boulevard in Woodhaven will include left-turn bays at eight intersections, fewer travel lanes, and longer pedestrian-refuge spaces.

“This redesign is going to make left turns on Atlantic Avenue much safer,” said Espinal. “It’s those turns that put pedestrians and drivers at the biggest risk of collision.”

The project, part of DOT’s “Great Streets” program, an effort to “rethink” four dangerous corridors across the city, also envisions raised bike lanes along the medians, the first lanes anywhere on Atlantic. That means East New York, a priority bicycle district with high numbers of cyclists killed or severely injured, but little access to the bike network, will finally have new cycling infrastructure.

“This side of the district doesn't have a lot of bike lanes, so while we continue to push for a comprehensive bike network, we have to also take the steps we can to protect bikers who use our streets without lanes,” Espinal said. “I'd love to see a protected bike lane along the Conduit giving residents safer access to Queens by bike, and a connection to the rest of Atlantic Avenue to Downtown Brooklyn.”

The city has struggled with fixing Atlantic Avenue ever since the death of a baby and two young mothers by a speeding, drugged-out driver in 2003, who plowed into the families near Logan Street in Cypress Hills, along the Brooklyn-Queens border.

Drivers kept killing pedestrians at such a rate that in 2010 the Daily News dubbed Atlantic “the Avenue of Death”: With 9 — count 'em, 9 — deaths along the avenue just between 2006 and 2008, the avenue emerged as one of the two deadliest streets in the city, according to a study by the Tri-State Transportation Campaign.

In an effort to stop the carnage, DOT finally named Atlantic Avenue the city’s first arterial “slow zone” in 2014 and included it a year later in the Great Streets program, which seeks to redesign the four arteries to prevent crashes, improve accessibility, and strengthen neighborhoods.

Unfortunately, progress to achieve those goals on Atlantic has paled in comparison to its Great Streets brethren, especially Queens Boulevard. This first phase of the rebuild, now under way on the 1.2 miles from Georgia Avenue to Logan Street in East New York and Cypress Hills, fails to deliver many improvements sought by safe-streets advocates. It offers pedestrians some help — bulbouts and higher-visibility crosswalks — but it doesn't impinge on the six full lanes now dedicated for vehicles. And DOT refuses to install any bike lanes here.

“Many of these interventions are designed to protect pedestrians from dangerous drivers, instead of implementing changes that would fundamentally alter dangerous driving behavior,” according to Transportation Alternatives’ 2016 report, “Atlantic Avenue’s Inequitable Crash Burden.”

On more affluent stretches of Atlantic, DOT has done a good job of improving specific intersections. For example, it redesigned Times Plaza — the perilous junction of Atlantic, Flatbush, and Fourth avenues in Downtown Brooklyn — last year, following a prolonged effort by safe-streets advocates and local elected leaders.

Atlantic Avenue offers unique challenges as a Great Street and Priority Corridor. Atlantic Yards construction, for example, could tie up progress in Prospect Heights for some time. The Long Island Rail Road, rising up between Bedford and Howard avenues in Bedford-Stuyvesant, constrains the street’s redesign in ways unlike most other corridors — but may provide opportunities for public spaces beneath elevated tracks.

These obstacles can be overcome, with the vision and commitment of residents, their elected officials, and DOT — and must be overcome to create the safe, equitable Atlantic Avenue we all deserve.

David Herman is a safe-streets advocate and co-chair of Transportation Alternatives’ Brooklyn Activist Committee. He tweets about Atlantic as @dhfixatlantic.