If you believe the companies developing automated vehicle technology, driverless cars could be on the market as soon as 2021. It will probably take a lot longer than that for real autonomous fleets to operate in cities, but government agencies are already anticipating how to handle the driverless car future. On Friday, the New York City Council transportation committee got in on the action.

While it may seem premature to plan for driverless cars, the interests involved are already staking out positions that will have implications down the line. Friday's hearing was a chance to see what the autonomous vehicle lobby wants from local government, and how the city wants driverless cars to fit into its transportation system.

At stake are not just the myriad public safety implications of putting computer-driven and possibly networked vehicles on city streets, but also the effects on motor vehicle traffic volumes and the footprint of private car parking.

"[AVs] could reduce demand for parking, free up urban space for other needs, whether for bus and bike lanes, parks and gardens, or more affordable housing," DOT Deputy Commissioner for Policy Michael Replogle told the committee. Alternatively, he said, the technology could lead to "ghost vehicles" across the city "driving around to avoid having to pay for parking."

New York state law currently prohibits driverless vehicles from operating on public roads, a cause for concern for Council Member Dan Garodnick.

"It does not feel to me like New York is really leading when it comes to automated vehicles," he said. "Even the notion that we should continue to support a law that would not allow even testing on public roads in New York state to me sends a message that we're not all that serious about innovation."

David Strickland, a former chief of the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration and a lobbyist for the "Self Driving Coalition for Safer Streets," whose members include Google, Uber, and Ford Motor Company, said the city needs a "thoughtful and consistent regulatory regime" if it wants to be at the forefront of testing and advancing the technology.

Unlike some autonomous vehicle boosters, Strickland never claimed that AVs would supplant high-capacity transit. Instead, he anticipates driverless cars completing "last mile" trips connecting people to transit. But when transportation committee chair Ydanis Rodriguez asked how driverless cars would affect the council's goal of reducing car ownership and usage, Strickland had no specific answer. He called it "the $64,000 question."

"There’s going to be multiple uses for this technology," Strickland said, including private ownership, trip-sharing, and even public transit. "I think it’s going to be, frankly, an all of the above."

Strickland never articulated why it would be advantageous for New York City to be an autonomous vehicle leader, however, other than the fact of being ahead of the pack. Is New York better off setting a template for autonomous vehicle regulation before other cities? Or would it be preferable to learn from other cities' mistakes first?

City officials, for their part, want to make sure the technology is proven before the vehicles are tested on NYC streets.

In his testimony, Replogle warned against rushing to pass legislation proposed in Albany to allow driverless cars to operate on New York state roads, citing the need for a "full urban safety review."

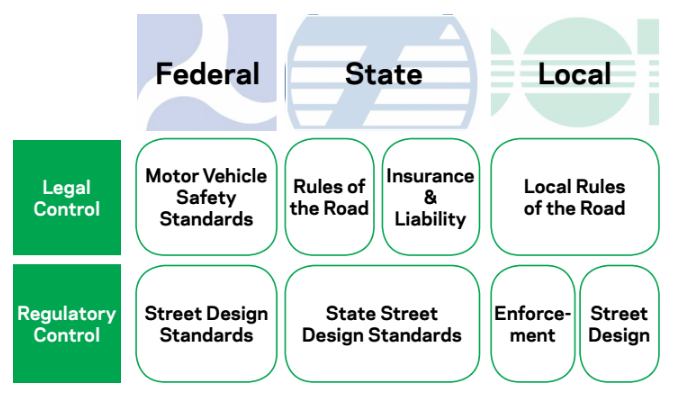

"We could see testing, but again, with the driver poised by the steering wheel," Replogle told council members, arguing that the city needs to be able to control how the vehicles are tested on its streets. "The city has had no voice in the federal regulations, and the state could well develop its own policies absent the voice of the city."