This is the second installment in a multi-part series looking back at the victory over the Midtown bike ban, 25 years ago. The first part provided an overview of the response to the ban. This post looks at that activism in the context of the previous two decades of bike advocacy. Activists are planning a September 28 bike ride and forum to commemorate and celebrate the events of 1987, and Streetsblog readers are invited to participate and contribute.

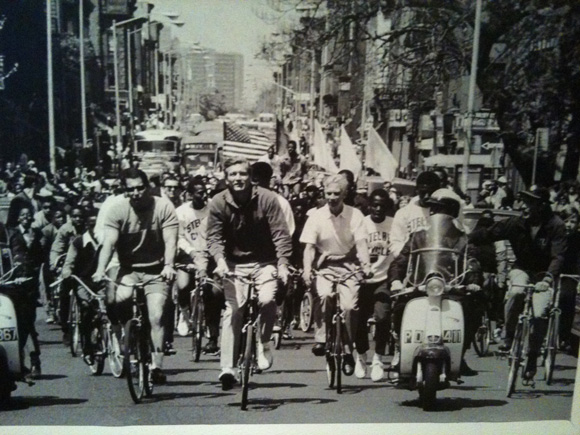

What would resonate for the cycling movement over the long haul was not just the victory over the Midtown bike ban but the insurgency itself, beginning with its fortuitous timing. The mid-eighties had been a low point for cycling advocacy. Over the prior two decades, biking in New York had grown in fits and starts, with three specific events raising cycling’s profile. The first was in 1966, when Mayor John Lindsay banished automobiles from the Central Park drives on Sundays and created the city’s first large-scale convivial riding environment. Next was the 1973 Arab oil embargo, which sidelined cars and taxis at filling stations and validated petroleum-free human-powered travel. Third and last was the 11-day transit strike in April 1980, during which bike-commuting briefly tripled and began to be viewed as a legitimate means of navigating the city.

But while these singularities put more New Yorkers on bikes, none ignited lasting expansion of the infrastructure to support them. In fact, amidst the city’s ongoing fiscal crisis, key links in the bike network were taken away. With bridges badly deteriorating, entire lanes were shut down, and bike lanes on the river crossings were often the first to go -- a stark reflection of the cycling community’s political impotence as well as an impediment to its growth. And as the city’s economy, but not its languishing mass transit system, rebounded from the 1970s slide, driving experienced its own boom. Increasingly, to ride a bike in these circumstances was not just to risk life and limb but to endure brutish and sometimes violent confrontations with drivers and their vehicles.

By 1987, cycling advocates badly needed a new cause to mobilize around. The bike ban turned out to be exactly that.

The Rebirth of T.A.

For years, New York activists and writers from Jane Jacobs and Paul Goodman to Ted Kheel and Pete Seeger had decried the automobile as an urban destroyer. Finally, in 1973, around the time of the oil price shock, an organization dedicated to reclaiming city streets from cars came into being -- Transportation Alternatives. The primary founders were NYC Earth Day impresario Fred Kent (later the founder of Project for Public Spaces), urban planner (and, later, Greenmarket founder) Barry Benepe, civic gadfly Roger Herz, urban scholar-journalist David Gurin, and transportation engineer Brian Ketcham, who was then finalizing the Lindsay Administration’s (and the country’s first) “transportation control plan” intended to meet air quality standards by reducing auto travel.

This quintet charged TA’s tiny staff with selling the public on the notion of urban bicycle transportation while instructing City Hall in the nuts and bolts of bike-supportive infrastructure. Neither effort met with much success, in part because the innovative and cycle-friendly Lindsay Administration had been followed, in 1974, by the hidebound clubhouse regime of Mayor Abe Beame. And in a city whose highways, subways and electrical grid were literally crumbling -- in which whole neighborhoods were being emptied and burned -- political space for bicycling was scarce.

Still, there were some triumphs.

In one notable victory in 1979, advocates won exclusive access to the Queensboro Bridge South Outer Roadway. Progress, however, was subject to sudden reversals. In the early 1980s TA labored to parlay the upsurge in bicycle commuting during the transit strike into permanent bike lanes on avenues, rehabilitated paths for cyclists on bridges, and assured bicycle access to offices. But this effort foundered, most notably when a hastily installed and indifferently maintained bike lane on Sixth Avenue went underused and was removed. The public mood soured and city government largely abandoned the idea of investing in bicycle transportation.

During this low ebb, in 1986, new leadership came into Transportation Alternatives, motivated by apprehension that the widening backlash against scofflaw cycling (though not against dangerous driving, which was killing a half-dozen pedestrians a week) would precipitate a crackdown. As it turned out, the revamped organization would have less than a year to begin reinvigorating itself -- internally, with a database of members and volunteers, a bimonthly newsletter, and regular meetings; and externally, through dialogues with city police and transportation officials, campaigns for safer bridge access, and grassroots evangelizing on bike safety and advocacy, much of it from curbside lemonade stands (“Free For Bike Messengers”) -- before the city invoked the nuclear option and unveiled the Midtown bike ban in July 1987.

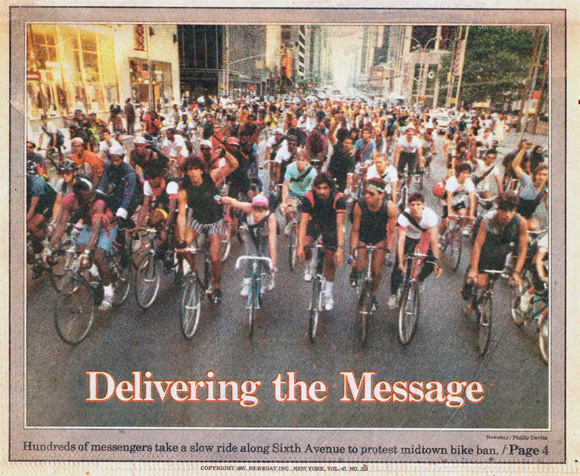

TA assuredly did not direct the uprising against the ban. Leadership came from the ranks of those whose livelihood was directly threatened, most notably in the person of Steve Athineos, a 31-year-old cycle courier with training in communications. Athineos had a commanding street presence, a gift for truth-telling sound bites, and street cred built from three years of messengering. Much of the coordination, flyers and banners for the protest rides emanated from the East Houston Street storefront of Steve Stollman, an intensely driven barmaker and pamphleteer schooled in radical movements and plugged into pro-cycling and anti-auto activism throughout Europe, the U.S. and Canada. TA and other local cycling organizations like American Youth Hostel and the NY Cycle Club along with the national League of American Wheelmen (now League of American Bicyclists) worked their modest political contacts and publicized the protest rides, as did some bike shops, most notably Bicycle Habitat, whose owner-manager, Charlie McCorkell, a former TA president, had a keen sense of cycling’s tenuous place in city politics.

Mostly, though, TA rode the wave and harvested the energy. For example, when the New York Times published an eloquent broadside, "Unfair to New York Bikers,” by a young freelance writer named Michele Herman, TA recruited her into the organization as a volunteer writer (and, years later, as lead author of TA’s NYC bike-plan book, The Bicycle Blueprint). Indeed, the floodtide unleashed in the uprising -- from the boxes of pro-bicycling letters sent to City Hall (which we accessed through a FOIL request) and the daily papers, to spirited meetings and connections made at the protest rides -- served as one big recruitment drive. When TA finally came to the fore, conceiving and prosecuting the lawsuit that overturned the ban, the reward was an infusion of credibility and, with it, new members, volunteers and contributors.

One constituency missing from the upwelling against the bike ban was the city’s environmental community. As TA’s new president, I thought I could count on the green movement’s legal representation and political support. Not only was bicycling a form of green transportation par excellence, but for a dozen years I had served these groups as an economic consultant on energy issues. I received a rude awakening. None of the prominent environmental organizations were willing to petition City Hall to withdraw the pending ban, much less litigate against it, perhaps in part because the DOT Commissioner charged with administering the ban had been hired from their ranks. The deeper truth, though, was that cyclists were urban pariahs and bicycle transportation was too far on the fringe. In the suites as well as on the streets, we were on our own.

Next week: How the protests changed "the equation in the streets."