Red Hook’s Traffic is One-Fifth Trucks, Vans As More Warehouses Arrive

Red Hook's truckpocalypse is real!

12:00 AM EST on December 12, 2023

A trucker drives down Beard Street in Red Hook near an Amazon warehouse.

More than one in five vehicles on Red Hook’s streets is a truck or a commercial van — well above rates in some of the city's busiest trucking corridors — showing the dire situation in the Brooklyn waterfront neighborhood that has become inundated with last-mile warehouses.

Hundreds of heavy haulers barrel through the neighborhood an hour, according to a preliminary study that Department of Transportation officials presented to locals Thursday night [PDF]. With more delivery facilities on the way, residents said officials are moving too slowly to rein in the e-commerce giants that use their streets as launch pads to deliver countless packages and goods to the rest of the city.

The agency found that nearly 21 percent of traffic on the neighborhood’s main drag, Van Brunt Street, are trucks and commercial vans like the ones Amazon deploys from its massive outpost on Beard Street.

Another hotspot is Bay Street, which cuts through the neighborhood's ballfields and the local recreation center, where some 50 big rigs roar down both ways per hour, 14 percent of the 360 total vehicles, according to agency stats.

The stunningly high rates exceed major crosstown Manhattan truck routes like 34th, 42nd, and 57th streets, which have a truck share of 13 percent, according to DOT data from 2021 [PDF]. The Manhattan Bridge, has 24 percent truck traffic, the highest share of big rigs on the roads in that borough.

On the nearby Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, which DOT describes as a vital freight corridor, about 10 percent of its 130,000 daily vehicles is truck traffic.

Locals have dubbed the influx of heavy haulers the “truckpocalypse,” and traffic has gotten so out of hand that one area entrepreneur said his friends are afraid to bike to the neighborhood, and instead order an Uber or take their chance with the slow buses.

“This is actually having real impacts on the city’s goals to shift transportation towards more environmentally safe modes of transportation,” said Matías Kalwill, a member of the Red Hook Civic Association.

The two-year DOT review will look into how many trips the new warehouses generate, but the city is in slow motion compared to the incoming local last-mile facilities that are set to more than double.

“Changes are happening now and they are happening fast,” Kalwill said. “What I didn’t see a hint is a vision of how to respond to the current crisis moment that we’re living."

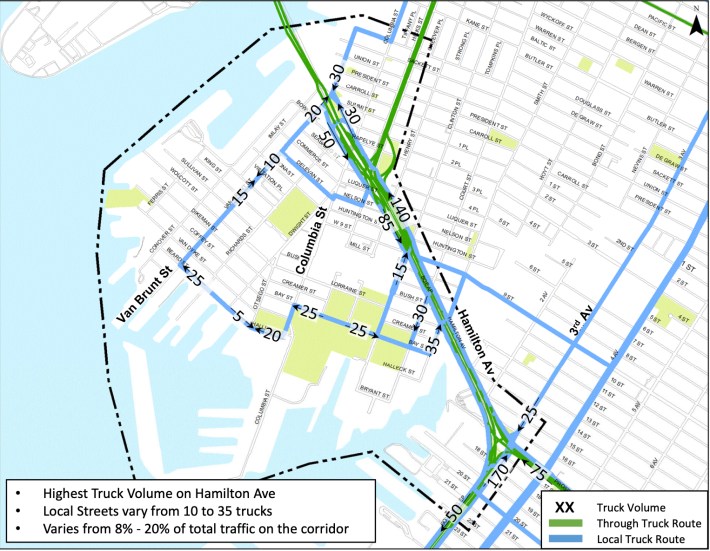

Across Red Hook, truck and van shares range from about 8 percent to upwards of 20 percent of traffic, according to DOT, and e-commerce companies deploy their vans in convoys of dozens out of their gates at a time, according to the agency's project manager of the study.

“What we’ve noticed is 10 to noon is when all of those sprinter vans are coming out,” said Harvey LaReau of the DOT. “They’re in fleets. The fleets that we saw were about 12 per and then every 15 minutes, and it was a 120 sprinter vans total.”

Lawmakers and advocates last year tried to stem the last-mile tide by seeking a zoning push that would require the warehouses get a special permit; right now they can simply set up shop "as of right" without public review in abandoned industrial lots that pervade low-income communities of color like Red Hook, Sunset Park, Hunts Point, Maspeth, Williamsburg, and Bushwick.

A similar effort in the state legislature would require such warehouses get a permit from the Department of Environmental Conservation showing they won't violate federal air quality standards.

These neighborhoods have already borne the brunt of pollution in the past from previous industrial uses and highways tearing through them, an unjust history that is now repeating itself to meet the needs of the same-day-delivery age, said Kevin Garcia, a transportation planner at the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance.

"They need hundreds, maybe thousands, of truck trips per day, and to have so many of these last mile distribution facilities in one area, that are clustered in these manufacturing zoned areas, is going to only increase the truck and overall vehicular traffic, but also increase the pollution and tail pipe emissions in those areas," Garcia said.

Red Hook residents's salaries are nearly 40 percent below the rest of the city on average, at a median household income of $71,078 compared to $113,315 citywide, according to Census data.

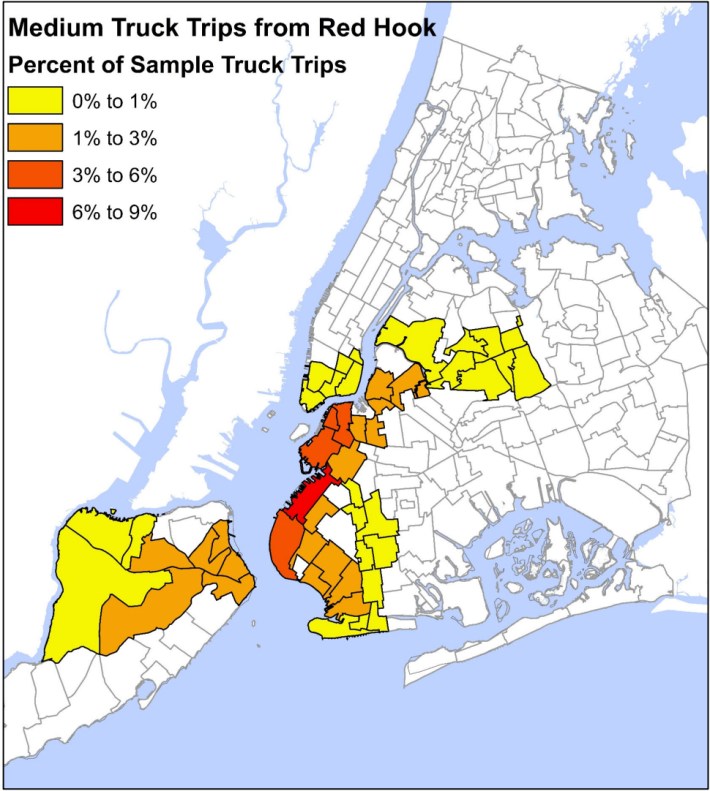

More than nine in 10 truck trips from Red Hook end outside the neighborhood, according to DOT. Drivers fan out predominantly to other industrial areas in the borough, as well as posher neighborhoods like Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope, Lower Manhattan, and suburban Staten Island.

On Red Hook's local streets, the agency counted between 10 and 35 trucks per hour in each direction, and a whopping 225 both ways on the highway-like Hamilton Avenue corridor beneath the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway that cuts the neighborhood off from the rest of the borough — or nearly four trucks a minute.

Total traffic on neighborhood roads ranged from 100-400 vehicles an hour during the morning rush on local roads to a whopping 3,410 in both directions of Hamilton Avenue. Meanwhile there are as many as 710 pedestrian crossings an hour at Hamilton and W. Ninth Street, which is one of the few paths in and out of the neighborhood connecting to the next-nearest subway station at Smith and Ninth streets in Gowanus.

Hamilton Avenue, with its Moses-era BQE viaduct roaring overhead and cutting off Red Hook from the rest of the borough, has long been a deadly divider. In early 2021 a hit-and-run driver fatally struck Imorne Horton who was trying to cross at Court Street, and the city has yet to make good on a redesign of the roadway from 2014.

There have been two traffic fatalities in the neighborhood since 2017, and pedestrian and cyclists injuries have risen 66 percent 113 percent between 2020 and 2022, respectively.

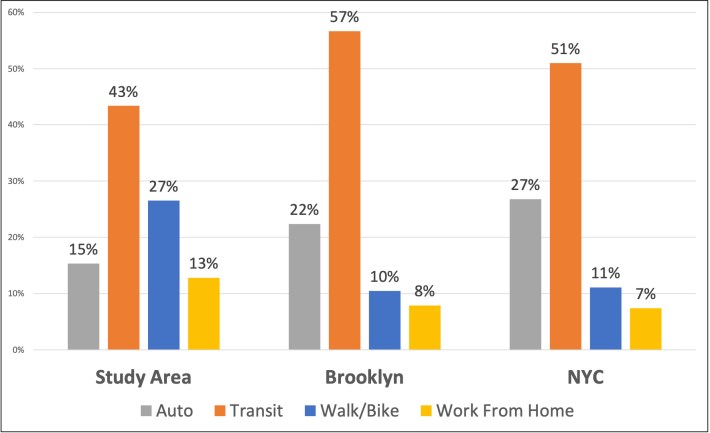

DOT launched the trucking and traffic study of Red Hook last year after online retailers began taking root in old industrial lots in the waterfront nabe, with two such facilities already active and three more coming, bringing more dangerous industrial traffic to an area where people walk or bike to get around at three times the rate of other Brooklynites, according to the DOT study.

More recently, the arrival of massive cruise ships has also saddled the neighborhood with toxic fumes from the ship’s exhaust and hundreds more cars transporting the ritzy maritime travelers to Manhattan.

That and the truckpocalypse have imposed dangerous conditions on the neighborhood, where the vast majority of people don't drive to work, despite no direct subway access.

The city must better organize the chaotic takeover of the streets by the big online retailers, said a spokesperson for a local merchants group.

“There needs to be more strategic partnerships and also vision within the city about the future of distribution locally. That is a vision that is lacking and so companies like Amazon take up and do what they want to do that’s easiest and cheapest for them,” said Carly Baker-Rice, of the Red Hook Business Alliance. “They’re just plopping it down because, hey, it’s land in New York City. They’re not looking at the fact that it’s on a peninsula or that there’s two streets out.”

More than one in five Red Hook residents works in the neighborhood, and 27 percent commute by foot or bike, nearly three times the borough-wide rate of 10 percent. Another 43 percent of locals take transit, and just 15 percent drive a car to their jobs, lower than 22 percent for all of Brooklyn.

The neighborhood’s 20 Citi Bike docks have been buzzing, logging a whopping 13,000 trips a month this summer — more than 400 a day — with the busiest stations on Van Brunt and Columbia Streets.

DOT plans to continue its study into next year, looking at how many trips that the last-mile warehouses generate, so they can better forecast traffic increases coming from incoming distribution centers. The agency will release more study findings between June and September of 2024, and publish a report in October.

The City Council last year passed a bill by Red Hook Council Member Alexa Avilés requiring the city to redesign its truck route and submit a report by September 2024, while three newer bills from earlier this year by the lawmaker for further city studies have yet to make it through the legislature.

City officials are also separately studying ways to mitigate the traffic caused by cruise ships, which have wreaked traffic chaos each time they’re at berth, and spew emissions comparable to 34,000 more trucks.

The city should go back to the waterfront area’s industrial roots and use the waterways to better distribute goods, said a local maritime supplier.

“Red Hook for the last 100 years ago and before, we always used our water for distribution,” said Jim Tampakis. “I’d want for the DOT to push Amazons and all these other distribution network companies to be able to assist them in using the water so that this way we can get all these trucks off the streets.”

These kinds of efforts to shift toward the water, also dubbed “blue highways,” have moved at a snail’s pace so far, with one barge facility planned for Manhattan’s Downtown Heliport not required to be operational until 2029.

Kevin Duggan joined Streetsblog in October, 2022, after covering transportation for amNY. Duggan has been covering New York since about 2017 after getting his masters in journalism from Dublin City University in Ireland. After some freelancing, he landed a job with Vince DiMiceli’s Brooklyn Paper, where he covered southern Brooklyn neighborhoods and, later, Brownstone Brooklyn. He’s on Twitter at @kduggan16. And his email address is kevin@streetsblog.org.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog New York City

Friday’s Headlines: Canal Street Follies Edition

Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine isn't happy. Plus other news.

Daylight Again: Bronx Community Board Backs Parking Ban at Intersections

The Boogie Down is down with daylighting!

Community Board Wants Protected Bike Lane on Empire Blvd.

Brooklyn Community Board 9 wants city to upgrade Empire Boulevard's frequently blocked bike lane, which serves as a gateway to Prospect Park.

The Brake: Why We Can’t End Violence on Transit With More Police

Are more cops the answer to violence against transit workers, or is it only driving societal tensions that make attacks more frequent?

Report: Road Violence Hits Record in First Quarter of 2024

Sixty people died in the first three months of the year, 50 percent more than the first quarter of 2018, which was the safest opening three months of any Vision Zero year.